The Legacy of Classical Architecture

Classical architecture has always stood the test of time, shaping the built environment of Western civilization for over two millennia. Rooted in the ancient traditions of Greece and Rome that date back even further, this architectural style emphasizes harmony, proportion, and beauty through the proper use of standardized elements and enduring design principles. While many figures have helped popularize and preserve these traditions over the years, including former architectural historian Calder Loth, the style itself transcends any single interpreter.

Defining Classical Architecture

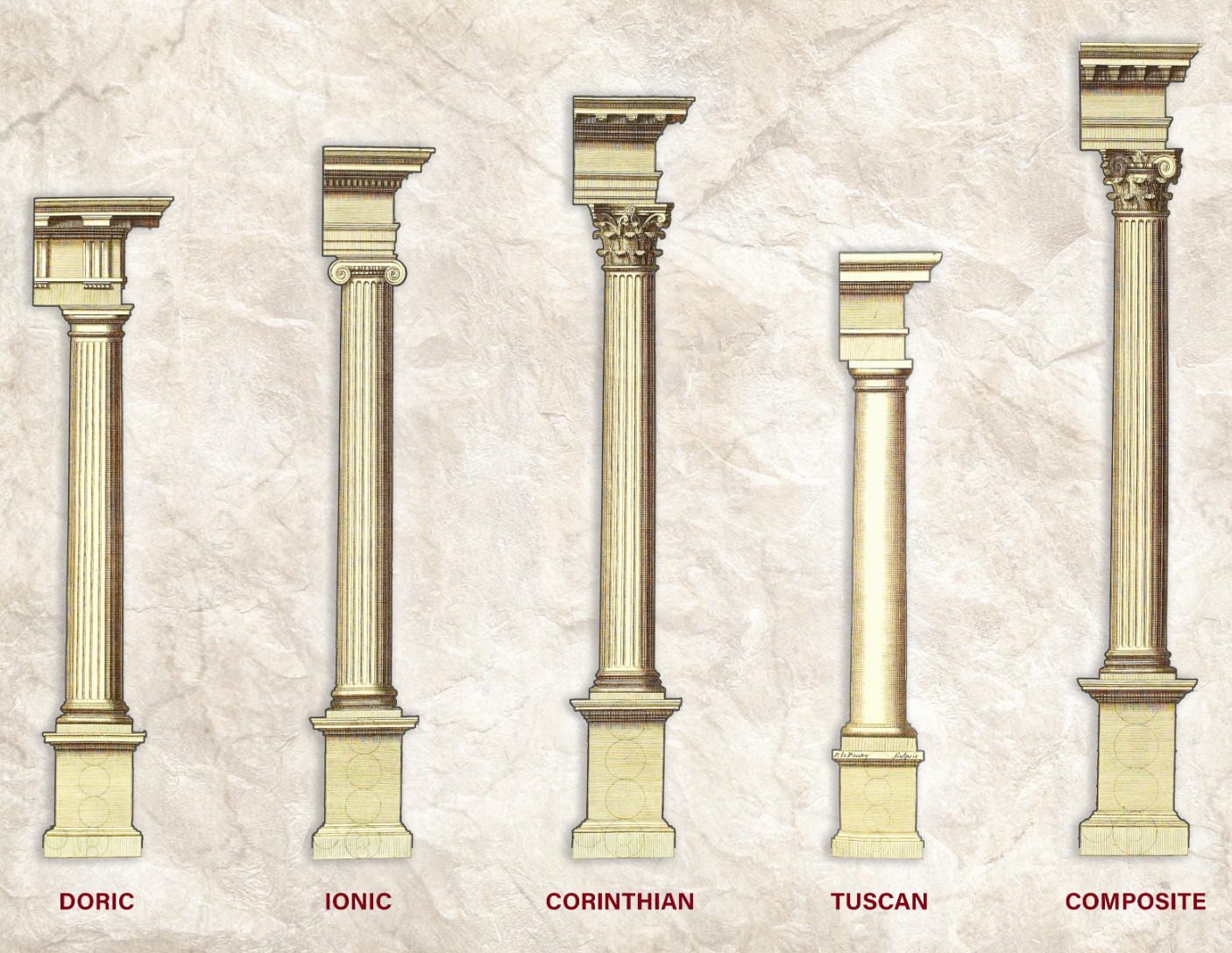

At its very core, classical architecture refers to the architectural styles and principles that were developed back in ancient Greece and Rome, as well as their subsequent revivals throughout history. It is not simply a matter of aesthetic tastes but also a system of rules, vocabulary, and design logic grounded in centuries upon centuries of precedent. Key elements include symmetry, clearly defined forms, and the use of classical orders—Doric, Ionic, Corinthian, Tuscan, and Composite—which are recognizable by their distinct column and entablature designs.

The United States Supreme Court Building, sporting Doric order pillars but with more of a Composite entablature. While the existing orders were considered standard and part of a set, more modern architecture splices some styles together for new designs.

Origins in Antiquity

The very roots of classical architecture lie in the temples and public buildings that survived the era of ancient Greece. Structures like the Parthenon exemplify the Doric order—sturdy, austere, and mathematically proportioned. Later, the Romans adopted and expanded this architectural vocabulary, refining structural innovations such as the arch, the vault, and the dome. They popularized the more decorative Corinthian order and introduced monumental infrastructure projects like aqueducts, baths, and amphitheaters.

Calder Loth’s series highlights how the Romans were not merely imitators but innovators who codified architectural practices. Their treatise—Vitruvius’s De Architectura—laid the groundwork for how architecture would be understood in the Western world.

The Classical Orders

One of the most defining features of classical architecture is the use of the orders, a structured system for columns and entablatures that also expresses a building's character and function. Each order has its own set of proportions, detailing, and symbolic associations:

Doric: The simplest and most masculine, associated with strength.

Ionic: More slender and elegant, often used for temples of goddesses.

Corinthian: The most ornate, symbolizing wealth and grandeur.

Tuscan: A simplified Roman version of the Doric, rustic and solid.

Composite: A Roman combination of Ionic volutes and Corinthian acanthus leaves.

Loth emphasizes that mastery of these orders involves understanding not just the visual forms but also their mathematical relationships and cultural meanings.

The column and entablature designs for each of the 5 classical orders used in Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome.

The Renaissance and Neoclassical Revival

After centuries of dormancy during the Middle Ages, classical architecture experienced a powerful rebirth during the Renaissance. Architects like Alberti, Palladio, and Michelangelo rediscovered Vitruvius and revived his classical principles with new interpretations. Palladio, in particular, was instrumental in codifying classical design for domestic architecture, influencing the construction in countless generations.

The 18th and 19th centuries witnessed the rise of Neoclassicism, especially in Europe and much so in the United States. It became the most preferred style for civic and institutional buildings, seen in landmarks like the U.S. Capitol and the British Museum. These structures are supposed to invoke ideals of democracy, rationality, and order. All of these are core themes of classical thought.

Composition, Proportion, and Ornament

Classical architecture is fundamentally about its composition. Buildings are designed with a very clear hierarchy, often with a central axis and typically symmetrical layout. Proportions, derived from humanistic ideals and geometric ratios, ensure that elements relate harmoniously to each other and the whole.

Ornament in classical architecture is not considered decorative excess but an integral part of the design system. From moldings and cornices to friezes and pediments, each little detail serves to reinforce the structure’s logic and aesthetic unity. Loth’s explanations often underscore how thoughtful ornamentation distinguishes true classical work from superficial imitation.

This image highlights classical ornamentation with intricate proportion and that showcases refined craftsmanship with lasting influence.

Classical Architecture Today

While modernism in the 20th century rejected many classical ideals, recent decades have seen a resurgence of interest in traditional design. Architects in the New Classical movement advocate for a return to timeless principles—craftsmanship, contextualism, and human scale.

Calder Loth, in his instructional series, serves as both historian and advocate, showing how classical architecture is not a relic of the past but a living language adaptable to contemporary needs. From urban townhouses to courthouses and campuses, classical architecture continues to offer a sense of dignity, permanence, and cultural continuity.

Conclusion

Classical architecture endures because it is built on principles that transcend time—order, beauty, and reason. Understanding its foundations, as illuminated by scholars like Calder Loth, provides not only an appreciation of historic buildings but also guidance for creating enduring architecture for the future. Whether you're an architect, student, or simply an admirer, the classical tradition offers a rich and rewarding legacy that continues to shape the way we build the world.